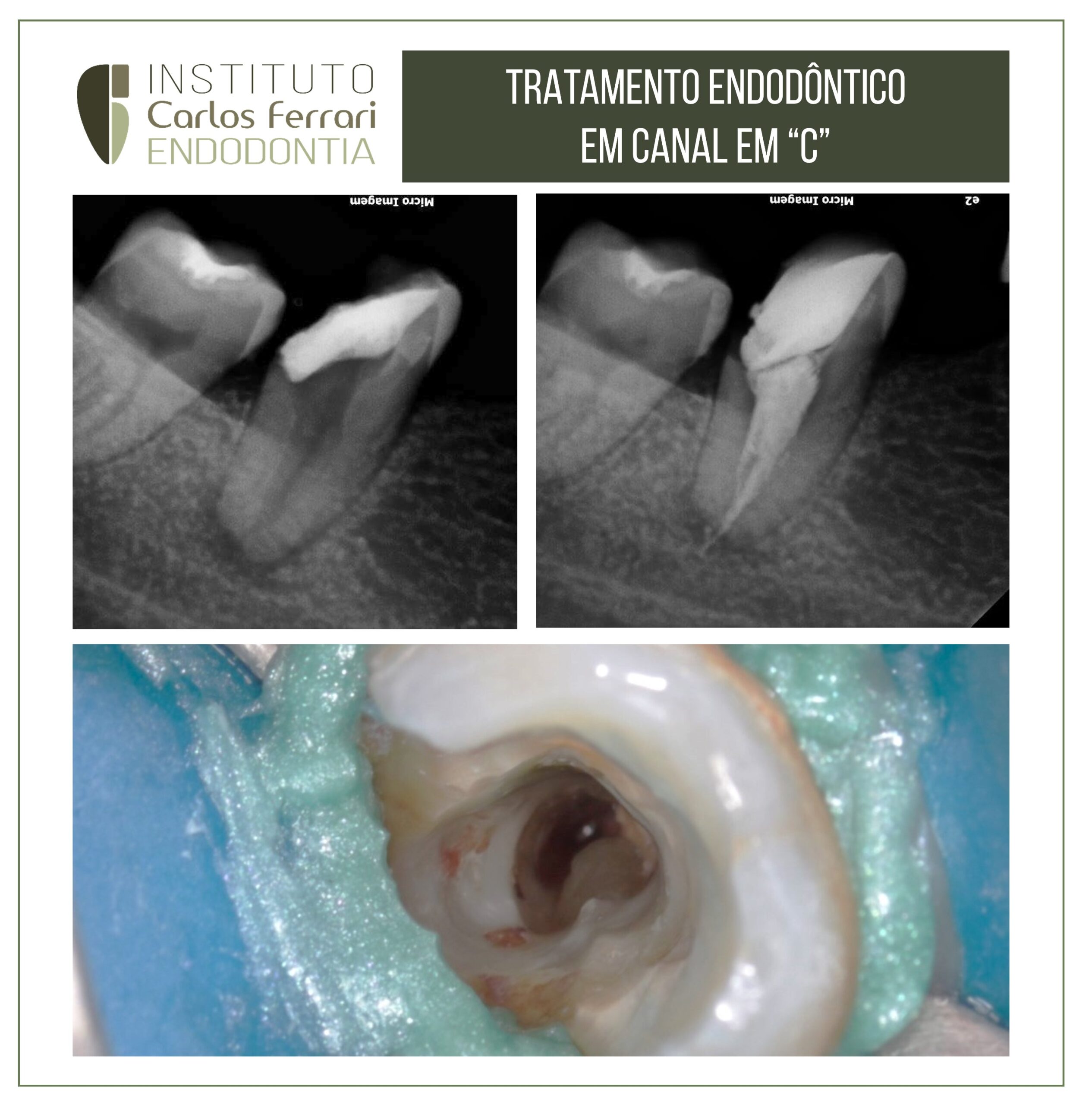

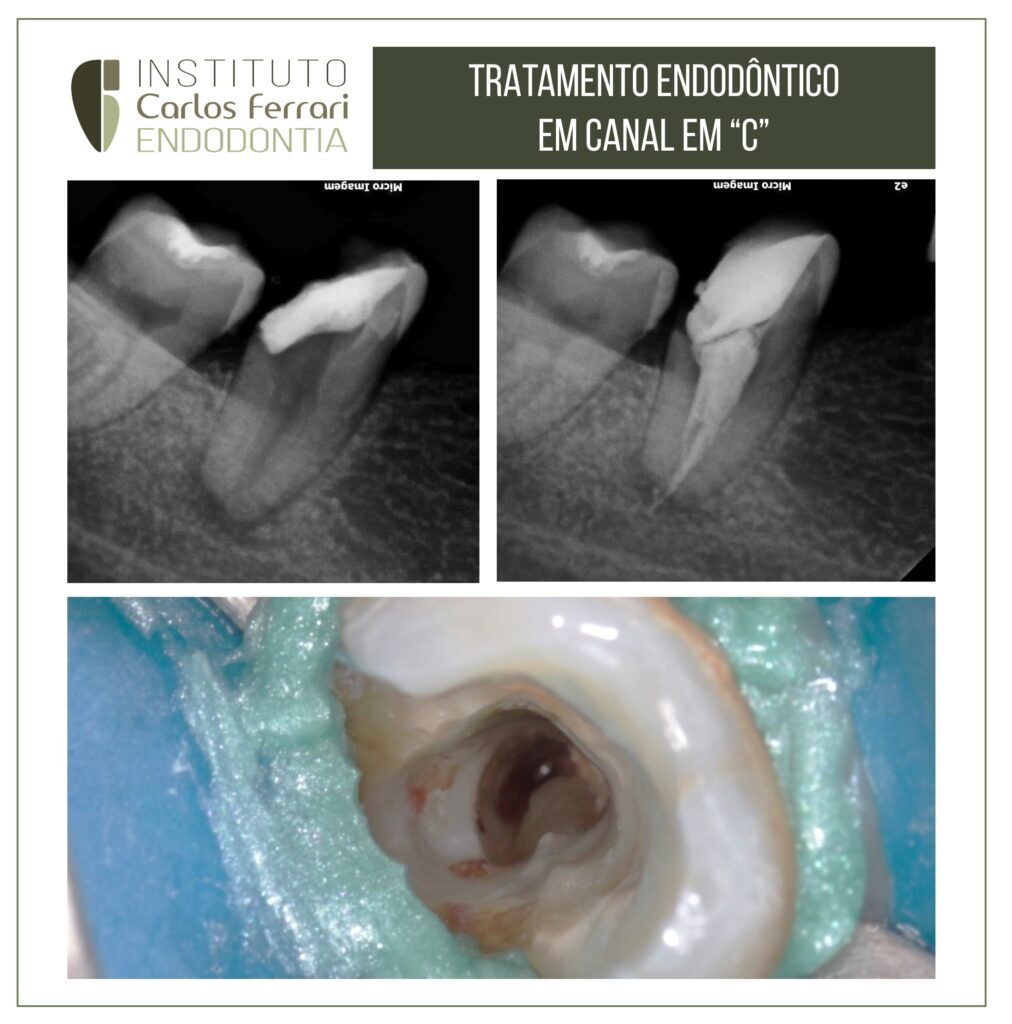

Endodontic treatment of a C molar. Anatomy in endodontics. Endodontic treatment carried out in a C canal in tooth 47, with pulp necrosis and asymptomatic apical periodontitis in a female patient.

Case conducted by students Vinícius Zuim and Lucas Moreira from the endodontics specialization program at Chibebe Cursos in Taubaté

Anatomy in endodontics. In: Marceliano-Alves MFV, Miyagaki DC, Linden MSS, Brasil SC, Dantas WCF, Alves FRF. Multidisciplinary Compendium in Dentistry 1: 45-51.

INTRODUCTION

The goals of endodontic therapy are the removal of organic debris, sanitation and three-dimensional obturation of root canals. In a classic work in the endodontic literature, Schilder40 (1974) introduced the concept of cleaning and shaping, i.e., cleaning and shaping the root canal, reaffirming the importance of continuous tapering from the cervical to the apical third, maintaining the original shape and position of the foramen.

The accomplishment of these steps is only possible with the knowledge of the pulp cavity anatomy, its normal aspects and, mainly, its variations, factors that guide the coronary opening, the location of the canals and the instrumentation. The variations in morphology lead to the use of the expression "root canal system" (RTS), and because it is in direct communication with the periradicular tissues through apical ramifications, collateral, accessory, delta and intercanal connections, lack of knowledge of anatomical diversity is one of the main causes of treatment failure.

In teeth with straight canals, the application of Schilder's40 (1974) principles is less critical; however, in curved canals, depending on the degree of curvature, the difficulties increase and may result in accidents, such as: deviation of the original path of the canal, perforations, zip, tears and steps. A tooth that has curved canals and presents the highest frequency of endodontic treatment is the lower first molar; thus, knowledge of its internal anatomy is imperative49. 49 These teeth have a mesial root and a distal root, but can have an accessory root in the distolingual region. In the mesial root, normally two canals are found (mesiobuccal and mesiolingual), but one to three canals can be identified. The distal root usually has one canal, but can have two.

Barker et. al.4, in 1969, after an anatomic study in mandibular first molars, reported a case of a mandibular first molar with a mesial root with three separate canals. They also considered that variations in shape and number of canals are greater in mesial roots, which appear as multiple canals and with communications between them.

As seen, the mesial roots of mandibular molars can present one, two or three canals and depending on the anatomy can be configured as a difficulty during canal preparation. Another complexity of these teeth is the cervical projection of dentin on the proximal wall of the mesial roots, which increases with time due to the deposition of secondary dentin. This structure leads to mesiodistal reduction of the pulp chamber, making it difficult to locate the entrance of the canals. This, added to the curvature of the canal, can restrict the movement of the file and produce a lever effect, culminating in wear on the outer wall of the curvature in the apical third and on the inner wall in the cervical and middle thirds.

Anatomy in endodontics.