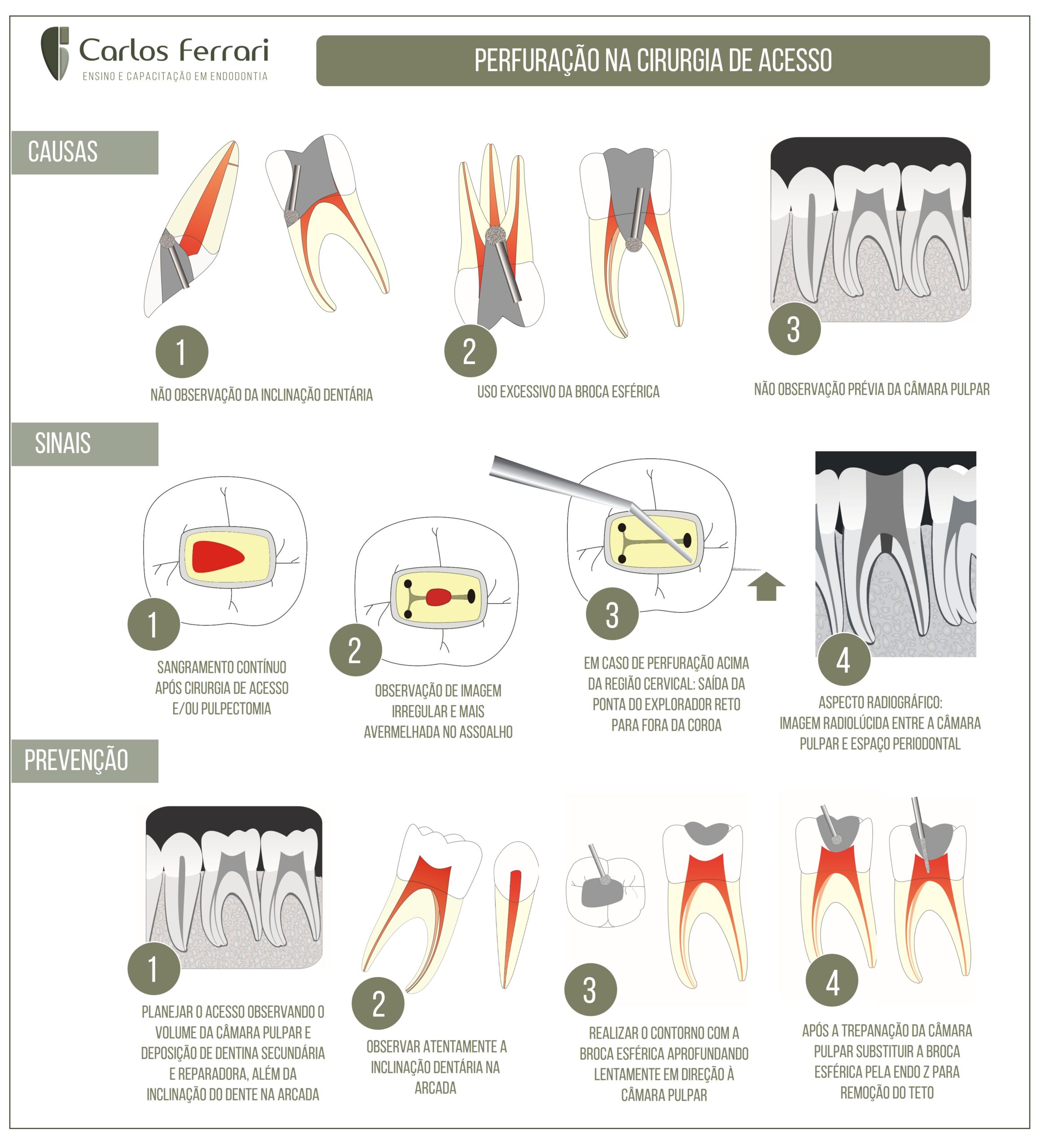

Perfuração na cirurgia de acesso. Causas, detecção de sinais de perfuração, e como prevenir esse acidente tão comum na prática endodôntica.

In: Ricardo Machado. Princípios Biológicos e Técnicos. Ed. Gen, 2022:

Perfuração coronária

Comunicação acidental entre a câmara pulpar e o meio oral e/ou tecidos perirradiculares.

Principais causas

Inobservância do grau de inclinação do dente e/ou instituição de inadequada direção de trepanação, uso de brocas de diâmetro incompatível com o volume coronário, inexperiência e/ou falta de habilidade do operador.

Medidas preventivas

A prevenção das perfurações coronárias pauta-se sobretudo, na instituição de um correto planejamento com base em um criterioso exame clínico-radiográfico, e em conhecimentos sobre anatomia e morfologia dental.

Diante de dúvidas, radiografias com diferentes angulações horizontais devem ser realizadas. Para casos ainda mais críticos, a tomografia computadorizada de feixe cônico (TCFC) proporciona a visualização tridimensional dos dentes sem sobreposição de estruturas anatômicas e maior riqueza de detalhes.

Após o acesso à câmara pulpar com broca esférica, recomenda-se a utilização de brocas com ponta inativa, como Endo-Z, 3082 e 3083, para determinação da forma de contorno. O preparo da entrada dos canais deve ser realizado com broca Largo ou instrumentos específicos (abridores de orifício, Orifice Shapers etc.).

Para dentes com câmara pulpar e/ou canais atrésicos, pode-se ampliar a abertura coronária para obter melhor luminosidade e visualização.9 Nesses casos, o uso de lupa ou microscópio operatório associado a insertos ultrassônicos e/ou brocas de haste longa é fortemente recomendado, bem como a aplicação de corantes para diferenciação entre os tipos de dentina, visando à execução de desgastes mais seguros. O acesso facilitado a canais calcificados tem sido alcançado a partir da “Endodontia guiada”. Para mais detalhes, recomenda-se a leitura do Capítulo 35, Endodontia Guiada por CAD/CAM – Endoguide 3D.

Diagnóstico

As perfurações coronárias podem ser identificadas por meio de sinais característicos, como dor quando a área é contatada (mesmo com o paciente anestesiado), sangramento, sensação de queimação ou gosto ruim relatados pelo paciente durante e/ou após irrigação com hipoclorito de sódio, além de leituras instáveis ou aparentemente incorretas fornecidas pelo localizador foraminal eletrônico.

Diante de uma perfuração coronária subgengival intraóssea, quando não há contaminação, o selamento/preenchimento deve ser imediato. Inicialmente, procede-se à limpeza química e mecânica da área com hipoclorito de sódio em baixa concentração (0,5%) e curetas ou pontas ultrassônicas, respectivamente. Após secagem com cones de papel absorvente, realizam-se a aplicação e a compactação do material selador com espátulas de resina e/ou calcadores de tamanho compatível com o da perfuração.

Diversos materiais já foram utilizados para o selamento de perfurações coronárias subgengivais intraósseas, como amálgama de prata, cimentos à base de óxido de zinco e eugenol, pastas de hidróxido de cálcio, cimento de ionômero de vidro, resina composta e SuperEBA – todos apresentam significativas limitações clínicas.16,17 O agregado trióxido mineral (MTA), desenvolvido na década de 1990, e outros materiais biocerâmicos mais recentes têm melhorado substancialmente o prognóstico de dentes acometidos por perfurações coronárias subgengivais intraósseas e radiculares (ver adiante).18 Isso resulta, sobretudo, de suas favoráveis características, como biocompatibilidade, capacidade de selamento, insolubilidade aos fluidos teciduais e estabilidade dimensional a longo prazo. Os mais recentes – Biodentine,26 MTA Repair HP,27 Bio-C Repair,28 NeoMTA29 e EndoSequence Root Repair Material30 – ainda apresentam vantagens como menor tempo de presa e maior facilidade de manipulação em comparação ao MTA.

Perfuração na cirurgia de acesso

https://ferrariendodontia.com.br/perfuracao-radicular-externa/