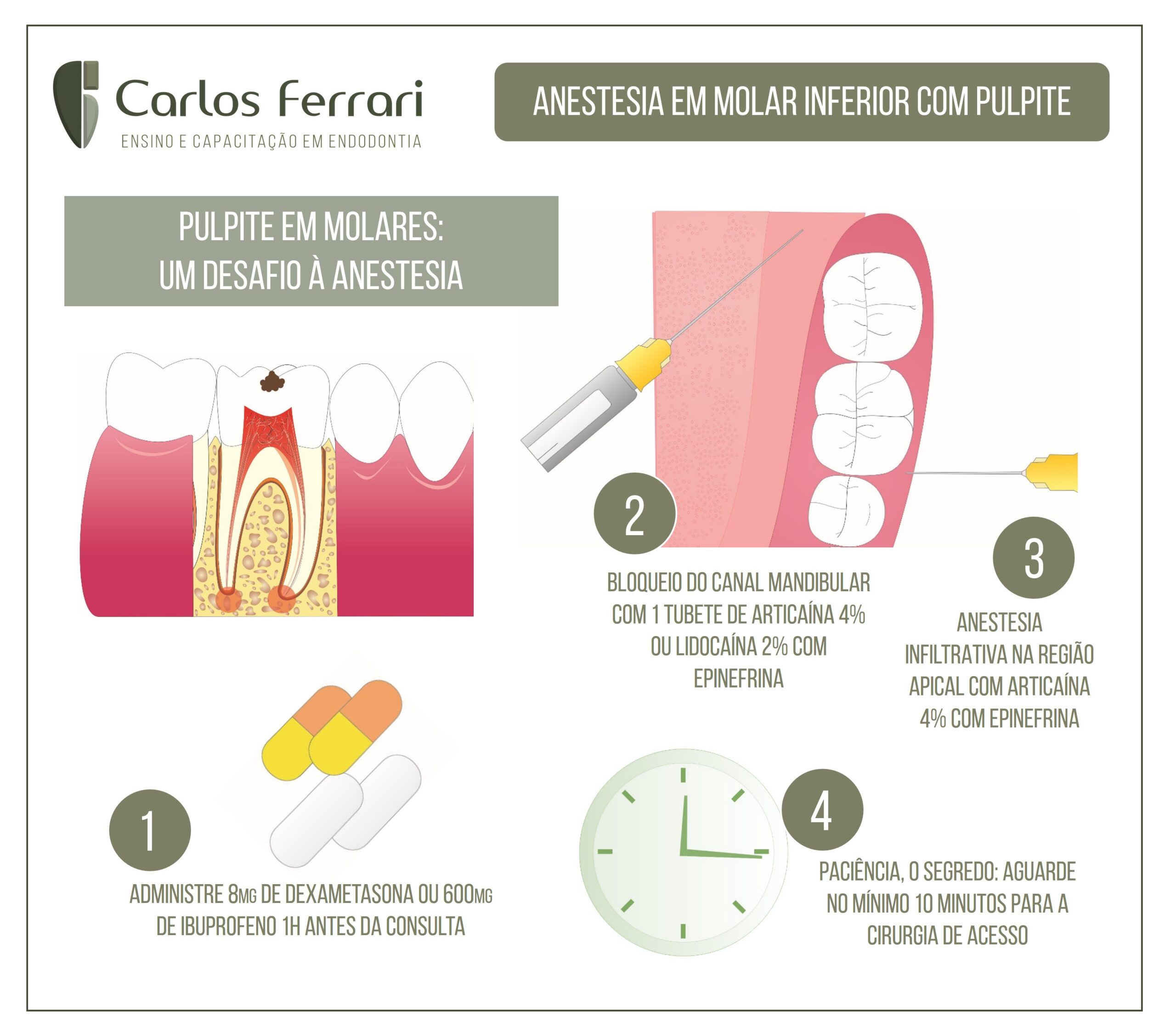

A anestesia odontológica em molares com inflamação pulpar irreversível é um desafio na prática clínica devido às dificuldades à sua completa realização. A seguir dicas para a realização com maior eficácia.

In Ricardo Machado. Princípios Biológicos e Técnicos, Ed. Gen, 2022:

Introdução

Nos tempos atuais, é inadmissível aceitar que o paciente sinta, tolere ou suporte qualquer tipo e intensidade de dor durante o tratamento odontológico, independentemente da especialidade em questão.

De acordo com a International Association to Study of Pain (IASP), “a dor é uma experiência sensorial e emocional desagradável associada a um dano real ou potencial dos tecidos, podendo ser descrita tanto em termos desses danos quanto por ambas as características”. É considerada uma experiência pessoal e subjetiva e sua percepção caracteriza-se de forma multidimensional, diversa tanto na qualidade quanto na intensidade sensorial, sendo ainda afetada por variáveis afetivo-emocionais.

Nesta definição, um trecho chama a atenção em especial: “experiência sensorial e emocional”. A dor tem sua fase sensorial (igual em todos os seres humanos na qual a técnica e a solução anestésica têm atuação direta) e emocional (mutável de ser humano para ser humano e no próprio ser humano dependendo da situação no momento ou das experiências vividas anteriormente relacionadas com o medo e a ansiedade – denominadas “variáveis afetivo-emocionais”). Portanto, para o total controle da dor, é necessário o domínio de ambas as fases. Caso contrário, ele estará comprometido.

Para o controle da fase sensorial, o cirurgião-dentista lança mão de injeções de soluções anestésicas com propriedades analgésicas por meio de técnicas específicas de anestesia. Já para atuar na fase emocional, o profissional deverá estar apto para condicionar seu paciente e até mesmo empregar meios alternativos de controle do medo e da ansiedade (técnicas de sedação oral ou inalatória e/ou hipnose).

O desmembrar da palavra “anestesia” corresponde à supressão de todas as formas de sensação (dor, pressão e tato) com perda da consciência, porém na Odontologia ambulatorial o cirurgião-dentista tem a condição de remover apenas o sintoma doloroso, o que nominalmente corresponde a uma analgesia (eliminação do sintoma doloroso sem perda de consciência). Para uma melhor compreensão deste capítulo, será considerada aqui a semelhança entre os termos: analgesia ≈ anestesia ≈ controle da dor.

A anestesia odontológica divide-se em dois tipos principais – local e geral –; o primeiro ocorre em regime ambulatorial e o segundo em ambiente hospitalar.

Em relação à anestesia geral, o cirurgião-dentista deve saber quando e como indicá-la. Não que ele não possa realizar procedimentos indicados sob anestesia geral (casos em que há contraindicações da anestesia local e realização de cirurgias maiores, como ortognáticas e de traumatismos faciais), mas entende-se que há uma especialidade médica para aplicá-la e, assim, deve ser realizada em regime hospitalar com os devidos acompanhamentos e cuidados.

Antes do início de qualquer procedimento e após a realização da técnica anestésica, os profissionais devem aguardar o que se conhece como período de latência (tempo necessário para o início do efeito anestésico) e averiguar os sintomas para, assim, terem certeza do sucesso.

Após a anestesia local ter se instalado, observa-se a apresentação dos sinais e sintomas, que se subdividem em subjetivos e objetivos. Os subjetivos retratam o que o paciente relata (como dormência, formigamento, sensação de “inchaço” etc.), e os objetivos, por sua vez, dependem da instrumentação do profissional no local (realização do tratamento sem sintomatologia dolorosa). Os sinais (observados visualmente pelo profissional como queda do lábio e da pálpebra) despertam pouco interesse para a demonstração da anestesia dental, uma vez que representam a ação do anestésico local em fibras nervosas musculares e não sensitivas responsáveis pela inervação dental.

Em suma, é importante entender que este capítulo aborda a anestesia odontológica muito além de técnicas de injeções anestésicas, e sim uma somatória de atitudes como controle de dor, em que se faz importante não somente a injeção correta, mas também o condicionamento psicológico do paciente para o perfeito silêncio operatório.

O cirurgião-dentista não deve esquecer de que o paciente ambulatorial consegue perceber tudo à sua volta (inclusive o tato e a pressão) e, se não for bem condicionado psicologicamente, seu cérebro o induzirá a pensar que não foi anestesiado e, por mais que se repita a anestesia, acrescentando-se mais anestésico, não se conseguirá “controlar” essa sensação.

Requisitos para a técnica anestésica

Antes de qualquer procedimento anestésico e/ou adoção de métodos de controle da ansiedade, o cirurgião-dentista deve obter informações importantes, por meio de um questionário com uma linguagem adequada, sobre o seu paciente e seu histórico completo de saúde, com detalhes sobre sua história atual, pregressa e familiar (anamnese).

A anamnese deve ser feita exclusivamente pelo cirurgião-dentista, e não por outro profissional auxiliar, ao qual se restringe apenas a realização de perguntas preliminares, como nome, idade, gênero, ocupação etc. Durante a anamnese, os seguintes fatores devem ser atentamente observados:

•Condição física e psicológica do paciente

•História de qualquer experiência anterior desagradável quanto a tratamentos odontológicos

•Sensibilidade a algum tipo de medicamento

•Estado cardiovascular

•Distúrbios respiratórios

•Distúrbios do sistema nervoso central (SNC)

•Deficiências metabólicas e distúrbios endócrinos

•Alterações hematológicas ou patológicas

•Obtenção do pulso e registro de sua frequência, volume e ritmo

•Registro da pressão

•Frequência e característica da respiração.

Anestesia mandibular

A anestesia mandibular é, sem dúvida, a mais difícil. Os dentes inferiores e seus tecidos adjacentes recebem inervação do III ramo do V par craniano – o ramo mandibular –; que apesar de ter uma constituição mista (motora e sensitiva), o maior interesse recai sobre as fibras sensitivas, que na região de face interna do ramo da mandíbula, se dividem e originam os nervos alveolar inferior, lingual e bucal. Na região do forame mentoniano, o alveolar inferior subdivide-se nos nervos mentoniano e incisivo.

É importante conhecer o trajeto nervoso, uma vez que, diante de uma inflamação e/ou infecção, por exemplo, faz-se necessária a associação de várias técnicas anestésicas.

Nervo alveolar inferior (intraósseo)

Desce atrás e ligeiramente lateral ao nervo lingual, entre os dois músculos pterigoides, e continua seu trajeto até alcançar a superfície interna da mandíbula, onde penetra no canal alveolar inferior por meio de um forame delimitado por uma estrutura anatômica denominada língula (espinha de Spix). Não tem contato com a mandíbula acima do canal alveolar inferior e é responsável pela inervação dos molares e pré-molares inferiores, bem como do tecido ósseo e do periósteo mandibular (tanto vestibular quanto lingual). Atravessa o canal mandibular e, na região de pré-molares (normalmente entre o segundo e o primeiro), divide-se em dois ramos terminais assimétricos: o nervo incisivo e o nervo mentoniano.

Anestesia odontológica.